This cultural dance was created in Kelantan, so why has it been banned there?

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn8

- Email14

- WhatsApp31

Imagine a situation where an angmoh tourist stops you on the street and asks you: what sort of cultural heritage does Malaysia have? Some of us might sarcastically reply “corruption and nepotism”, while others might lead him to the nearest mamak stall and order a nasi lemak ayam goreng plus two roti kosong extra garing.

Others may look up to the sky and put a finger on their chin while they remember watching one of those old “Visit Malaysia” ads on TV. Cue a random montage of people in sarongs flying waus, sunset on a beach, some local dances, shadow puppets, kuda kepang, gasing, and a mishmash of other typical Malaysian scenes playing out while Siti Nurhaliza serenades a song in the background. Of particular interest is this particular scene:

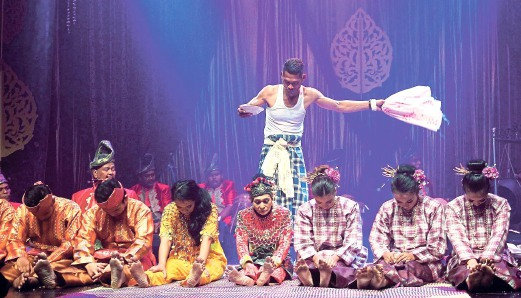

At first glance, it seemed like some sort of traditional dance… and not much else. Most people won’t even know the name of it, much less the Malaysian state it’s from and the fact that out of all the things you’ve seen in your flashback montage, it’s the only Malaysian tradition that made it into UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity so far.

In other words, the freaking UN wants to protect this particular Malaysian culture out of all the others. What’s so special about this dance? For starters, it’s a dance-drama called Mak Yong, and…

It was banned in Kelantan, where it was born

We wrote about wayang kulit and other performing arts being banned in Kelantan before, where we spoke to Eddin Khoo, the founder of Pusaka, an NGO that works hard to keep these old arts alive in today’s Malaysia. Mak Yong is one of the banned arts. In 1998, the Kelantan state assembly passed the Entertainment and Places of Entertainment Control Enactment, which prohibits “un-Islamic” local traditional performances such as Mak Yong, wayang kulit, and Main Puteri, to name a few.

Mak Yong is believed to have existed in Kelantan even before Islam came knocking, which was sometime in the late 1300s. In its original form, Mak Yong has a mystical element to it, associated with healing by shamans, trance-dance and spirit possession. So, yeah, that was pretty un-Islamic. The late former Kelantan menteri besar, Datuk Nik Aziz Nik Mat, had said that these elements needed to be purged if the community were to be purified.

“At that time, the clergy class had just taken over PAS. They wanted to show a change, to show the public how Islamic PAS is after taking over Kelantan. Datuk Nik Aziz may have been sincere to God, but many among the leadership wanted to show how these arts were against Islam.” – Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Hassan, political analyst, for Malay Mail Online.

But alleged paganism wasn’t the only issue. Eddin Khoo revealed that another reason these arts were banned was because some contains elements not permissible in Islam, such as revealing costumes and cross dressing. Women seemed to bear the brunt of the ban, as Muslim women are not supposed to be seen on stage. He also revealed that while the bans were there on paper, they were rarely imposed, but this still discouraged people from performing due to the stigma.

“He (the late Datuk Nik Aziz) understood that society operates at different levels, so while these traditions were banned, the bans were rarely imposed. In my, and Pusaka’s case, they were never imposed. For me, however, I didn’t bother with the ban itself. It was done in a somewhat gestural manner…more noise than substance.” – Eddin Khoo, founder of Pusaka, for Cilisos.

Imposed or not, a ban is still a ban, and it concerned the UN. Karima Bennoune, UN’s Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, had expressed her concern on the ban and asked the Kelantan government to lift it, saying that there should be measures to explain and make people understand the meaning of these practices to overcome prejudicial views about them.

Despite the UN’s pleas, the Kelantan government had stated that they will stick to the ban, but if anyone wants to perform these arts outside of Kelantan, they have no problem with that. However, the arts risk losing their very essence this way.

“Everybody should be able to enjoy it (the arts) and people must learn to value and appreciate native cultures that have been around for centuries. Simply moving the practice of these art forms elsewhere, away from the very region where some of them emerged, is insufficient to guarantee cultural rights,” – Karima Bennoune, for FMT.

Which is probably why…

The Mak Yong is dying, and revival may be difficult

Some Mak Yong practitioners have described the art as ‘bagai kerakap tumbuh di batu‘, a proverb roughly meaning that it still lives, but it’s no longer there. Some had said that it’s ‘hidup segan, mati tak mahu‘ (too lazy to live, but unwilling to die). Norzizi Zulkifli, director of the Mak Yong Titis Sakti, a Shakespearean-based Mak Yong theatre (we’ll get to that later), had said in an interview with Cilisos that Mak Yong performances are very rare nowadays, and years can go by without a single performance.

The ban in Kelantan may have had a hand in the dying state of Mak Yong. There was a time when Mak Yong was an integral part of many a Kelantanese’s life, performed for healing and merriment. With the ban in place, Mak Yong still lives on outside of Kelantan, but it’s no longer what it originally was. Certain factors such as cultural homogenization and time have turned a ritual performance, which is something essential to a society, into just a performance, something optional.

People have to go out of their way to discover Mak Yong, and Mohamed Ghouse Nasuruddin, an arts professor emeritus at USM, pointed out that many people no longer watch Mak Yong or wayang kulit for entertainment.

“When you institute this kind of ban, these art forms will die of neglect because it is no longer an integral part of society. Kelantan should promote it as part of tourism, as part of a performance structure,” – Mohamed Ghouse Nasuruddin, for FMT.

Ghouse also admitted that it would be difficult to revive dying arts, due to the people knowing them dying out without being able to pass on the knowledge to the new generation. With the cards stacked against them, how can they survive?

Old cultures risk being outdated, but they can adapt to the times to stay relevant

In recent times, we have seen traditional arts being remixed into something new, but they still retain their essence. Wayang kulit performances, for example, used to narrate epics adapted from Hinduism, and narrated fully in Kelantanese dialect. There used to be food offerings to the spirits during and after a performance as well. Today’s wayang kulit have evolved, with storylines based on local folklore and modern tales, and Tok Dalangs (the guy moving the puppets and narrating) now also incorporate standard Malay, English and even Bollywood songs in their storytelling. These changes managed to lift the ban on wayang kulit.

Mak Yong Titis Sakti, of which Norzizi is director, is an example of evolving art. While at its core the theater stayed true to the traditional form of Mak Yong, it is based on a foreign text, William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer’s Night Dream, plus other changes. It was first shown in 2009, and since then it had been selected as the only Malaysian work to be included in the Asian Intercultural Shakespeare Archive, as well as being studied at the National University of Singapore. Early last year, she directed another Mak Yong fusion theater, based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, called the Throne of Thorns.

If you want to see what Shakespeare Mak Yong looks like (or just Mak Yong in general), you’re in luck, because Mak Yong Titis Sakti had been given a facelift and will be staged again in the near future.

- Where: The Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Center (KLPAC)

- When:

- 27th January (8.30 pm)

- 28th January (3 pm)

- 1st, 2nd, 3rd February (8.30 pm)

- 4th February (3.00 pm)

- How: You can book your tickets through this link.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn8

- Email14

- WhatsApp31