Whoa, there are Malays on this Aussie island.. and they want indigenous status?

- 356Shares

- Facebook317

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn4

- Email3

- WhatsApp28

If you’re always on social media, chances are you might have seen one or two articles about Malays in an Australian Island. And maybe, you may also have Googled about these people.

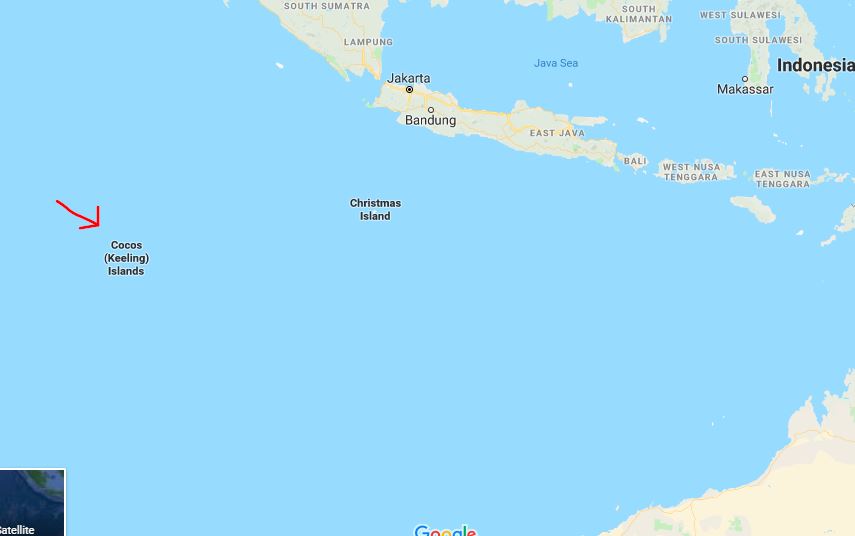

Well, in case you missed out, there’s a tiny set of islands known as Cocos Islands (named Cocos because it had lots of coconut trees [Cocos nucifera]).. and it has a Malay community known as Cocos Malays, just like how South Africa has Cape Malays (which we’ve written about some time back).

But we’re not gonna cover those basic facts about Cocos Malays lah. We actually found out that, similar to the Malays here, Cocos Malays also want their bumiputera rights… in Australia?! But wait, there’s a reason and it’s probably because…

The Malay labourers were the FIRST people to live in Cocos

The Cocos Islands are also known as Keeling Islands because, long before the Malays came to Cocos, the islands were discovered by Captain William Keeling in 1609. But Cocos remained uninhabited until the 19th century, when merchants John Clunies-Ross and Alexander Hare separately landed on Cocos’ shores.

Clunies-Ross checked out Cocos in 1825 when he was looking for a place to settle and left with plans to return there. Then, Hare and a group of people on his ship landed on Cocos in June 1826, hence setting up the first settlement on Home Island (one of the islands on Cocos). The first settlers consisted of mostly Malays from various places in the Southeast Asian region including Penang and Malacca.

Since many local groups around the world have reportedly succeeded in getting indigenous recognition on the basis of first inhabitants, you could say that it would be fair for the descendants to seek indigenous status since the first generation of Cocos Malays were technically the first known inhabitants of the islands.

When Clunies-Ross and his family came to Cocos in February 1827, they found Hare there, who by then settled 2/3 of the islands. The Hare and Clunies-Ross families tried to get along but couldn’t because they fought over territory and finance.

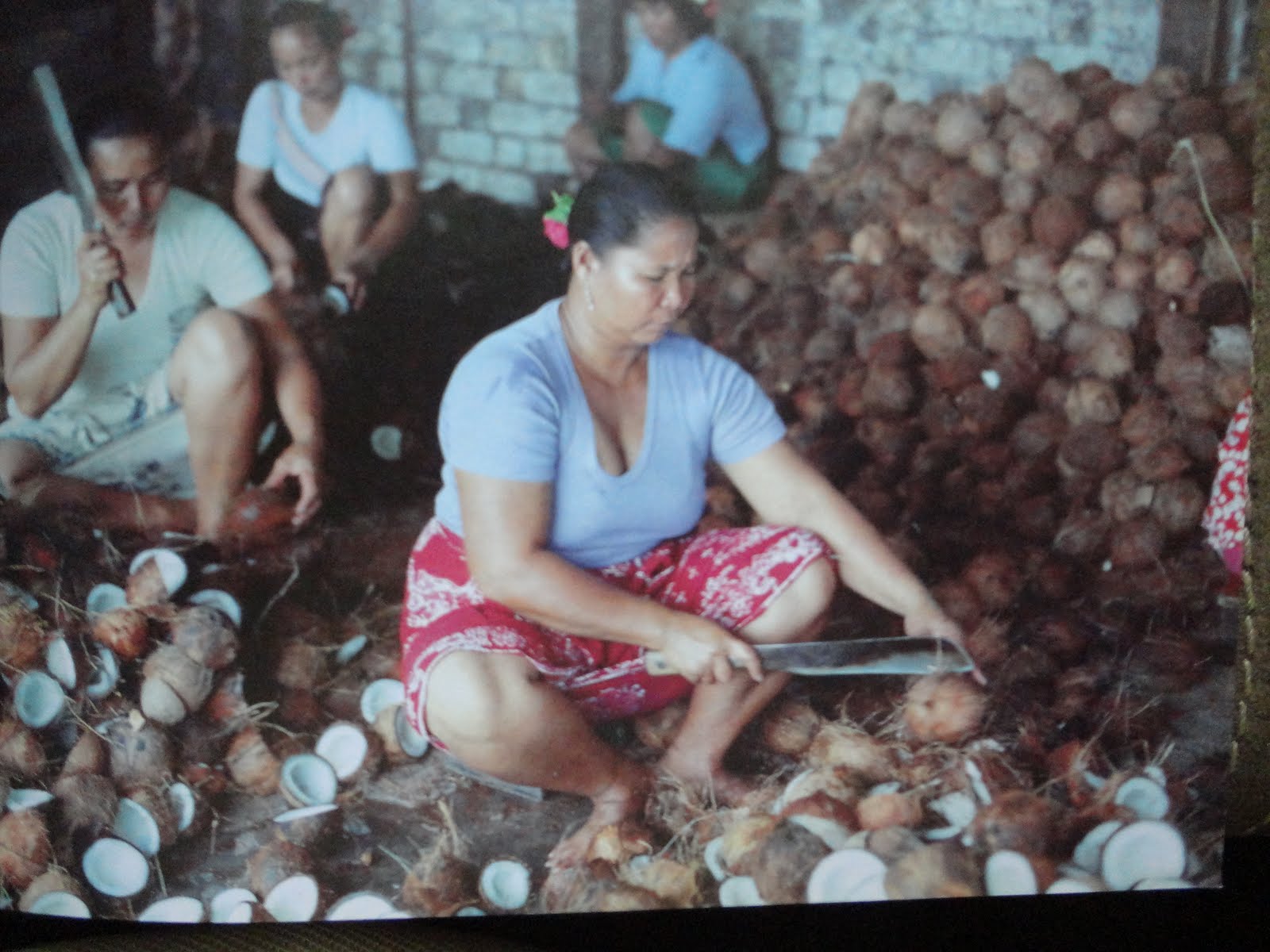

Since the disputes got worse, Hare moved to Batavia by himself. As a result, Clunies-Ross successfully ran a coconut estate business empire with help from Malay labourers in harvesting coconuts for consumption and export, and took control of Cocos.

For some time, Cocos was famous for its thriving coconut industry (mainly coconut husks a.k.a. copra), but the demand for copra didn’t last forever, so no more business lah. And it wasn’t just the coconut business that lost its reign.

World War 2 was a time when many Cocos Malays were forced to migrate to Christmas Island, Western Australia, Malaya, Singapore and North Borneo. That’s why you’d find that there’s actually a Cocos community in Sabah. :O

Meanwhile, the Clunies-Ross dynasty controlled the Cocos until 1978, when the Aussie govt bought all the islands from the last Clunies-Ross “king” and slowly started making some changes for the Cocos Malays.

However, life on beautiful Cocos isn’t exactly paradise

In the 1980s, the Cocos Malays were given the chance to vote on their political status, where they chose to be Australian citizens. While Australian citizenship has its perks, it also allows the Aussie govt to have absolute say over the islands (duh!), which have put Cocos Malays at a disadvantage. For example, the ban on hunting booby seabirds, which was a staple in their diet, meant that they cannot hunt and cook this staple dish anymore.

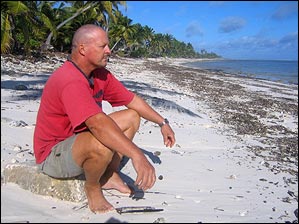

And as we stated earlier, descending from the first known inhabitants of the islands probably made them see themselves as indigenous Australians. But what is really pushing them to seek indigenous recognition? Well, for one thing, John Clunies-Ross, a clam farmer who is the son of the last Clunies-Ross “king”, said that there’s a misconception about life on Cocos:

“I suppose people think we are living on a resort, and it is beautiful but it’s so much more than that… In some ways it is hard for us the way it is hard for people trying to get things done in a remote indigenous community — there is the language issue, transport is hard, there are communication problems and the challenges of remote administration.” – said Clunies-Ross.

The push for indigenous recognition could be linked to the need for economic help, as the Cocos economy relies heavily on the govt services sector and a small tourism sector. Among the various economic problems that Cocos faces (apart from high shipping and transport costs) is unemployment, which actually dropped from 6.7% in 2011 to 3.8% in 2016. Oh, that’s actually… good.

Similar to our local Bumi rights, getting indigenous recognition could be seen by them as a ticket to getting better economic opportunities since the Aussie govt funds indigenous-specific services like grants, uni courses, housing assistance, employment and school programs, to address social, health and educational issues that indigenous people face due to policies and services that weren’t helpful to them (affirmative action lah basically).

So, will the Cocos Malays get their Aussie bumi rights?

A documentary titled Australia’s Forgotten Islands (2017) showed Cocos Shire Council leaders Balmut Pirus, Clunies-Ross and Aaron Bowman going to Canberra to seek declaration of indigenous status. They met the Northern Territory Labor senator Malarndirri McCarthy, who is herself an Aboriginal (Yanyuwa). Apparently, she agreed with their call for indigenous recognition.

“Are they indigenous to the Cocos? And I think probably, you know, an obvious answer would be, ‘Well, yes’… It really does come down to perhaps the definition of indigenous and that’s a question I think that will be debated for some time.” – said McCarthy.

Although Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion was hesitant in discussing this call, he agreed to meet the Cocos Shire Council delegation since the govt acknowledged the Shire Council’s progress in lowering the unemployment rate.

“He (Scullion) seems to understand what we are trying to do and I hope he can help us. If we can solve unemployment while we help Cocos grow bigger that is a major achievement. We want to make our island a place where kids can see a job for themselves in the future.” – said Pirus.

At the same time, the Cocos Shire Council also created a Strategic Community Plan 2016-2026 to improve the lives of Cocos Islanders.

Although we had difficulties finding more recent news updates on these efforts, we found out that the Aussie govt is working on making constitutional reforms known as “Uluru Statement from the Heart” to recognise the unique status of indigenous communities in Australia. They plan to intro an indigenous body in the Australian Constitution (“First Nations Voice”) and a “Makarrata Commission” to supervise the process of making things right between the indigenous communities and the govt.

To make these reforms, the Australian people will have to vote (in a referendum), which might be held after the May elections. This could mean that the Cocos Malays will have to, at least, wait till May for decisions on their call for indigenous recognition to be addressed.

So, now that you’ve reached the end of this article, here’s a little reward…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0AOGeqOnFY

Well, it’s not exactly Cocos Islands-ish, but hey, got coconuts.

- 356Shares

- Facebook317

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn4

- Email3

- WhatsApp28