Malaya’s D-Day: The massive WW2 invasion of Malaya that almost happened

- 425Shares

- Facebook384

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn5

- Email9

- WhatsApp19

Anyone who’s studied WWII history or watched Saving Private Ryan will no doubt be familiar with Operation Overlord, where Allied soldiers stormed Normandy Beach in 1944 on what is famously known today as ‘D-Day’.

In the D-Day invasions, the Allies threw everything but the kitchen sink at the Germans, deploying 156,000 troops, 11,590 aircraft, and 6,939 naval vessels to take the beach, in what would be the turning point for the war in Europe.

But it is little known that in Asia around the same time, plans were in motion to execute a similar operation to retake Malaya from the Japanese. However, this operation never happened. Why? Read on…

In early 1945, Japan was losing its grip in Southeast Asia

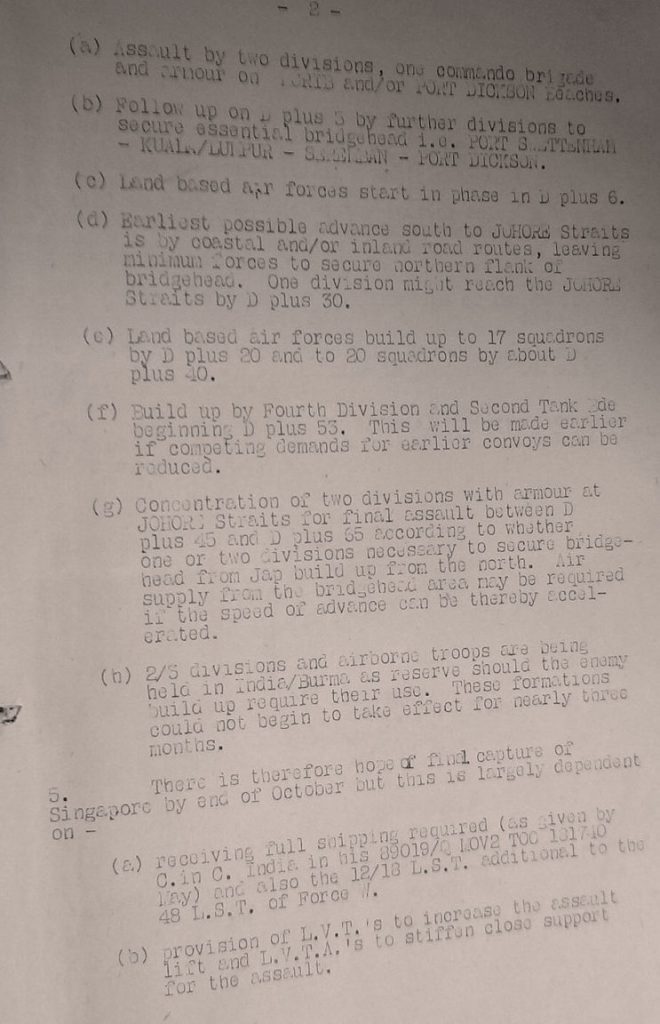

The British, having forced the Japanese out of Rangoon (the then-capital of what is today known as Myanmar), now had their sights set on doing the same thing in Malaya. These strikes were to be known as Operations Zipper, Mailfist, and Broadsword. It was to be a massive multi-pronged amphibious strike on Malayan soil which would involve more than 100,000 Allied troops with naval, armor and air support.

With the Japanese having just lost Burma, they were now in a very vulnerable position which the British wanted to capitalize; proposing to launch Ops Zipper and Mailfist in late August 1945, just three months after taking Rangoon from the Japanese.

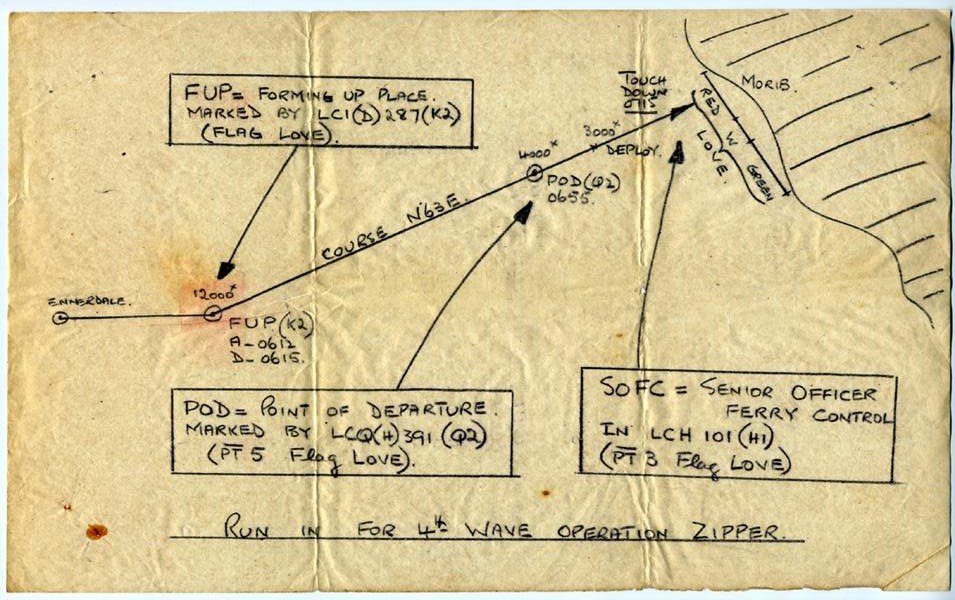

Op Zipper would move to first capture Thai airbases on the island of Phuket, before taking an airfield in Morib, capturing Port Swettenham (today known as Port Klang), and eventually Port Dickson. After that, Op Broadsword (a northwards sweep from KL to retake the rest of Malaya) would be carried out, while Op Mailfist (which wasn’t really a plan with exact details, and relied on the success of Zipper) would set out southwards to retake ‘Shackle’ (the codename for Singapore) by ‘hopping’ across the Johor Strait with one armored division supported by commando and parachute units.

But the Japanese were on full alert for an invasion on Malaya

With Burma lost, British planners correctly warned that the Japanese would anticipate that the Brits would press their advantage with an early assault on Malaya, with the ultimate goal of retaking Singapore.

Despite being unsure of the site of the initial strike, the Japanese already had 59,000 troops stationed in Malaya, a number which British planners anticipated would rise to 72,000 by the time Op Zipper was due to commence. And they were more than correct; in fact, a larger force than was expected had gathered in South Malaya. What’s more is this was around the time the Japanese started employing the infamous ‘kamikaze’ tactic, so there was now a ‘threat of attack from ‘suicide boats’ and ‘suicide aircraft’. Besides that, the Brits were short of naval vessels, so they would need additional time to gather enough support from the sea.

The Brits also suffered a major scare when three Malay members of Force 136(led by Capt. Ibrahim Ismail) were captured and tortured by the Japanese. But thankfully, through unbelievable acting skills, Capt. Ibrahim managed to turn triple agent and led the Japanese on a wild goose chase, convincing the them that the Zipper attack would happen elsewhere – which is a heck of a story in itself, and one we’ll be sure to write about next time.

Anyway, the British planners decided to do the smart thing and delay Op Zipper to 9th September 1945, much to the chagrin of British officers in India; who were overheard complaining that ‘there would not be any loot left’ once the operation started.

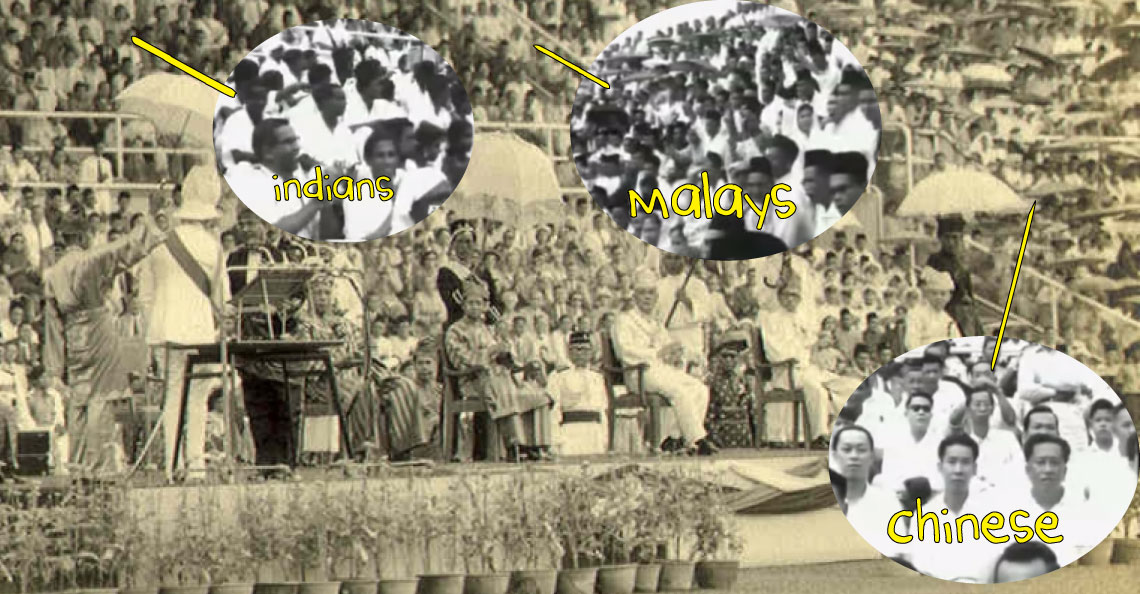

In any case, in terms of ground troops, the British were more than ready for the invasion – having amassed over 100,000 soliders made up of multiple Indian divisions, the 3rd Commando Brigade, and one parachute brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division (some of whom had, incidentally, also fought at Normandy on the actual D-Day). On top of all of that,

As we detailed in a previous article, Op Zipper was of particular interest to a certain Pattani prince named Tengku Mahmud Mahyideen; who wanted to use the success of Zipper to retake Pattani from Thailand, who at the time were allied with the Japanese. So, on top of the British forces, Tengku Mahmud’s local Force 136 guerrillas had infiltrated the south of Thailand and were also on standby for the actual strike.

And no, Tengku Mahmud is not related to a certain ex-Prime Minister (as far as we could find).

However, everything potong stim when the Japanese surrendered

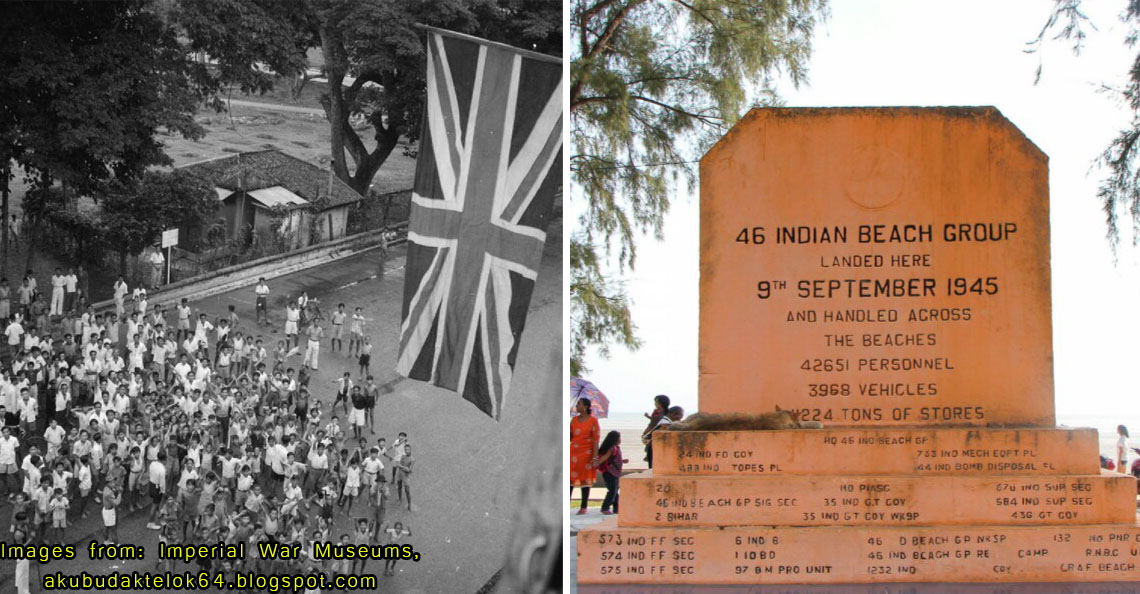

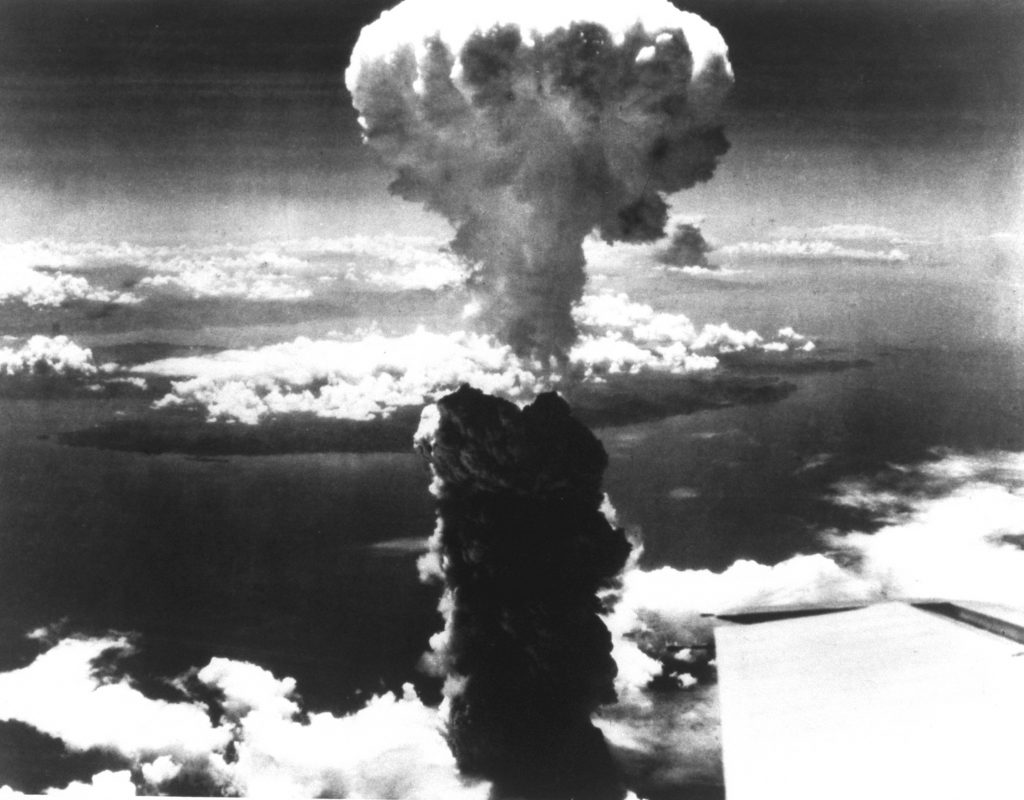

Following the atom bombs and the resulting Japanese surrender on August 15th 1945, the Brits chucked the two operations out the window, replacing them with downscaled versions named Operation Jurist (to retake Penang) and Operation Tiderace (to retake Singapore).

On the 1st of September, after being served a ‘Singaporean curry’ (which was described as ‘unrecognizable’ by the Malay sailors, for obvious reasons) on board the HMS Derbyshire, the British navy entered Penang without any resistance. The local Japanese commander surrendered his garrison to the British before fainting and having his sword taken as a souvenir by military policemen), and the Brits officially retook administration of Penang; celebrating by tossing Senior Service cigarettes into the local crowds.

Three days later, the Brits retook Singapore uncontested as well, although the surrender didn’t go down without some friction. One reason is kinda expected: The local Japanese commander General Seishiro Itagaki was furious at being given the humiliating task of surrendering Singapore. But the other reasons were the most Japanese things you can think of: British officers arriving to the surrender meeting dressed in crumpled, unwashed battledress (they left India at short notice and there was no washing water on board their ship). And in what was probably the worst offence, it is said that when a Japanese officer told them they were two hours late, the Brits responded with ‘We don’t keep Tokyo time here’.

Following the Japanese surrender, British POWs in Singapore were liberated to scenes of jubilation and music:

“… the P.O.W’s lay in their bunks with tears in their eyes. Even now I can see it all — and how a boy chorister could do what all the Japanese had tried to do for four years… Gradually the walking skeletons filled out — they even liked rice pudding especially with pineapple!” – as quoted from Roy Leadbetter, sailor on the British Merchant Navy ship Almanzora

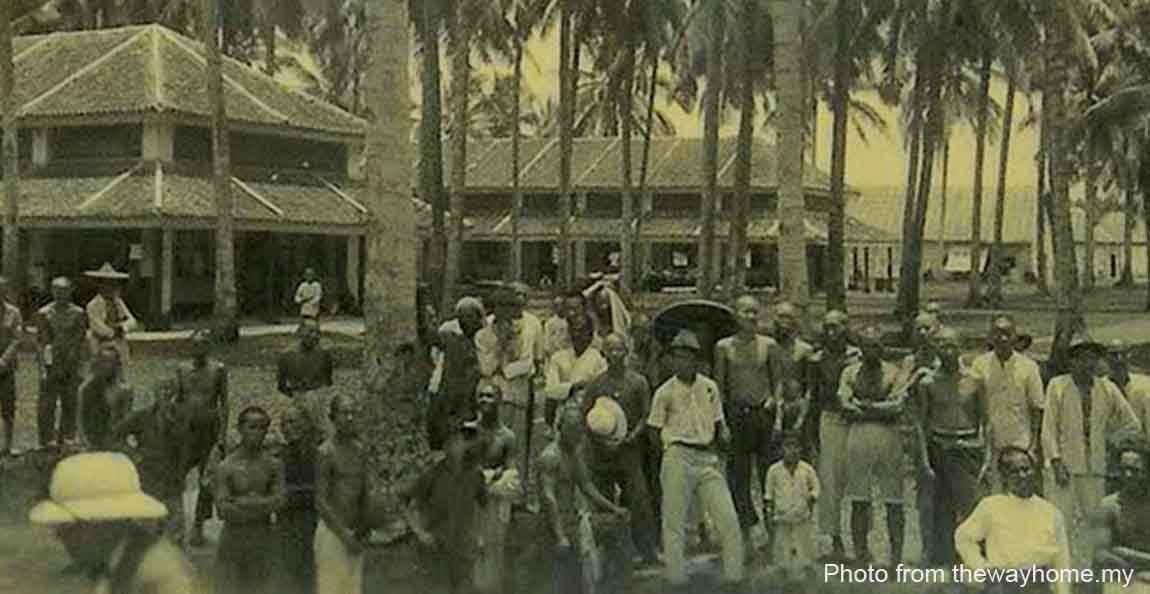

And finally, on September 9th, 1945, 46 British Indian Army battalions landed on the beaches of Morib, Selangor (again, to no resistance), and 6000 Japanese soldiers surrendered in Kuala Lumpur a few days after.

Despite all the planning, perhaps it’s best the Operations never happened

It is often said that the atom bomb saved more lives than it took. Regardless of where you stand on that issue, many lives would probably have been lost had Operations Zipper, Broadsword, and Mailfist actually been carried out. In fact, because of the surrender, the Allies had also canceled a similar land invasion of Japan itself called Operation Downfall, which might have resulted in even more casualties.

While everyone remembers the heroics and horrors of D-Day, many Malaysians never knew how close we were to being part of it had the Japanese not surrendered. It is perhaps fortunate then, that those plans for invasion remained nothing more than plans.

- 425Shares

- Facebook384

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn5

- Email9

- WhatsApp19