Despite too many medical graduates, Malaysia is seriously lacking specialist doctors… why?

- 3.1KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn18

- Email28

- WhatsApp88

The Health Ministry wants to do a lot of things, like giving every Malaysian access to quality healthcare, upgrading both medical facilities and the people who work in them, and another thing we’re not mentioning here. However, a huge obstacle stands in their way: they don’t have enough specialists.

“In particular, the ratio of clinical specialists of 3.42 per 10,000 population is currently much lower than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) average of 14.13 per 10,000 population. Adding to the problem, of the approximately 8,000 clinical specialists in the country, more than 40% are in private practice, serving 30% of admissions into the country,” – Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad, Health Minister, as reported by The Sun Daily.

In case numbers give you a headache (you should see a specialist for that), the number of specialists we have are wayyy lower than international standards, and a lot of them work where they’re less needed. Just name a specialization, and we probably don’t have enough of that. Cardiology? Check. Rehab physicians? Check. Orthopaedic surgeons? Check. Oncologists? Check.

With the Malaysian population growing like it needs to see an oncologist, we need more specialists now than ever before. So why don’t we just train more then? After all, as the health director-general Datuk Seri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah said back in April,

“Once we have the quantity, then we can talk about the quality… If you do not have enough medical students, you do not have enough house officers and medical officers, then you cannot expect to have enough specialists in the country,” – Datuk Seri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah, as reported by The Star.

Um… about that…

We may actually have too many medical students

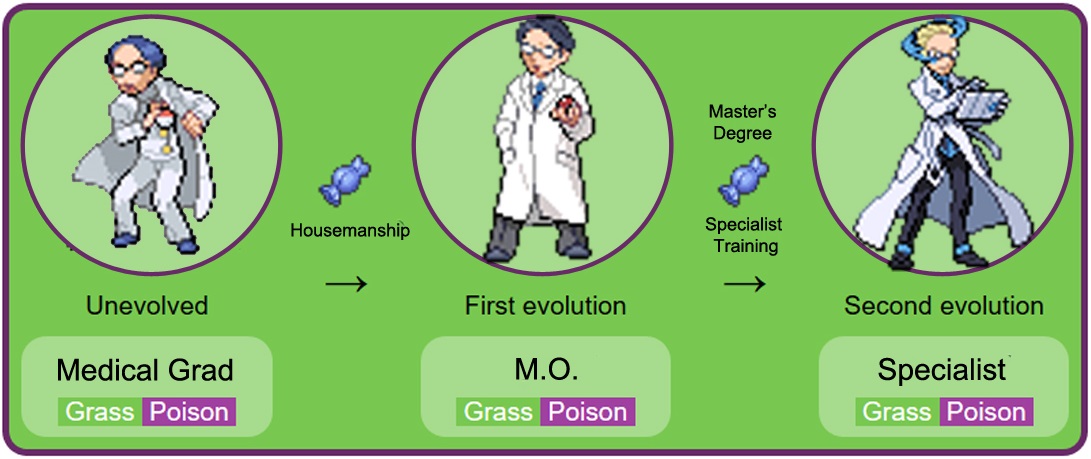

The medical profession is a mystery to most of us, but here’s how it typically works in Malaysia. After graduating with a Medical Degree, medic students can’t fix people up yet because they don’t have a license. To get that, they have to intern at select government hospitals in a process called housemanship, where these graduates are known as house officers, or, as the cool kids gender insensitive say it, housemen.

Completing that will promote the house officers to Medical Officers (MOs), but they’re not specialists yet (but you can probably ask them MC already). To be a specialist, MOs have to go back to school and do their Masters’ degree, and after some training, voila! They’re now specialists. So yeah, to have more specialists, the logical thing for the government to do would be to train more doctors, wouldn’t it? If 1 out of 100 doctors eventually become a specialist, having 10,000 doctors should give the government 100 specialists. Simple maf.

However, as any medical student waiting to get a housemanship will tell you, Malaysia has more doctors than it can train. You can read our article on that issue here, but basically sometime in the 2000s the government went cray cray with the medical hype and approved a bunch of medical schools and medical courses overseas, making medical education much more accessible to the children of demanding Asian moms everywhere.

“We have an Air Asia ‘everyone can fly’ syndrome – it seems that everyone can become a doctor. Adopting Henry Ford’s industrialisation of car production to training doctors will result in poor quality medical practitioners,” – Datuk N.K.S. Tharmaseelan, president of the Malaysian Medical Association (MMA) in 2013, to the Star.

At one point, we were (and still are) producing somewhere between 3,500 to 5,000 medical graduates per year, but when the Education Ministry presented the graduates to the Health Ministry, we imagine the Health Ministry went white and said “We ain’t got the space for all that!” See, using the AirAsia analogy, the Education Minsitry lowered the price of plane tickets by a lot, but the Health Ministry didn’t buy more planes.

As you remembered from the first two paras, to get a license graduates have to intern at selected government hospitals, but the number of hospitals available for housemanship stayed almost the same all these time. But squished them in they did, and according to news reports, back then housemen had to take care of 15 hospital beds. A houseman is now said to only take care of three. A specialist used to supervise five housemen at a time. Now they have to take care of 20.

Resulting doctor quality aside, there’s still a pretty long queue to intern at a hospital, which could take graduates up to eight months to get in, during which their medical knowledge slowly erodes. And in this business, that eight months is pretty important, as…

The time taken to become a specialist can get unnecessarily long

Can you guess how long it takes to become a specialist in Malaysia? Let us put it this way. If your brother has a baby when you start your medical degree, if you’re lucky (or work very hard) you might be financially secure enough with your specialist salary by the time your niece needs a guarantor for her first house loan.

A Medical Degree takes five years, a housemanship two years, then three years of contract work in a government hospital, four years of a Masters’ Degree, then another two or three years of specialist training. That adds up to about 17 years of running around wards, studying, research and long shifts, but things do not go that smoothly for everyone. Remember the first bottleneck during housemanship? There’s a second one if you want to be a specialist, and that’s applying for a Master’s Degree. Currently, there are only about 1,000 slots open to some 3,500 MOs applying to further their studies each year.

That’s another line to wait in, which could add a few more years to your specialist journey. According to Prof Dr Zaleha Abdullah Mahdy, PPUKM’s Faculty of Medicine’s dean, this long wait is the reason why medical graduates don’t feel like becoming specialists. And subspecializing (becoming, say, a brain surgeon in addition to a regular surgeon) can take even longer.

“It takes 10 or more years from qualifying as a doctor to become a specialist and more if one subspecialises. For example, a cardiologist is a physician specialist in internal medicine who subspecialises in the heart, while a brain surgeon is a specialist surgeon who goes on to specialise in brain surgery,” – Dr Sng Kim Hock, president of Association of Specialists in Private Medical Practice Malaysia, to the Star.

The Health Ministry produces about 1,000 specialists each year, but these are spread out over 30 different subspecialities, and not every field produce as many specialists as the other. For example, a 2017 report cited that only 25 to 30 doctors manage to become cardiologists each year. If you think that number is as meager as it gets…

The number that stayed in gomen hospitals is even lower

Datuk Seri Dr S Subramaniam, former health minister, revealed that last year alone, 170 medical specialists resigned from their government posts, which is an increase from the year before that. In more relatable terms, the Health Ministry loses around 3% of its specialists each year.

“Most of those who resigned were medical specialists of Grade UD54 and above, who have a lot of experience and are highly skilled. It is a big loss for us,” – Datuk Seri Dr S Subramaniam, to Malay Mail.

The number of specialists produced each year, as we said before, is roughly 1,000, but that number is stretched thin replacing the ones that resigned as well as filling posts as lecturers at higher education institutions, where there is also a shortage. As for why they resigned, well, it was believed that these specialists sought greener pastures in the private sector as well as overseas. Is this a problem? As a 2014 review puts it, Malaysia’s public healthcare serves about 65% of the population, but only 20-30% of specialists work there.

One reason for the migration is the income disparity between the public and private sectors. Obviously, private specialists earn more, and to address that the government had last year allowed government specialists to take a day off their duties each week to earn some side money, either through medical research, teaching or working part-time in the private sector. The Full-Paying Patient (FPP) scheme, which we had wrote about before, was also a measure to raise the income of government specialists.

The other reason is promotion prospects. Earlier, we quoted Subramaniam as saying that most of the ones that resigned are from Grade UD54 and above… which used to be the highest pay grade for government specialists. Basically, they reached the ceiling already, so there was not much going on in terms of promotion. The government introduced Grade UD56 in 2017 to address the problem, but the problem remains, as the higher you go, the less spots are available. Some will have to wait up to 10 years for a promotion.

Also, there’s bureaucracy.

“Bureaucracy is not a small issue. In the government it’s a big issue. Even if you want a promotion, there is bureaucracy there. Biasness. This is why specialist doctors and doctors, they are fed up and give up their jobs,” – Datuk Seri Tiong King Sing, then the Bintulu MP, as reported by the Malay Mail in 2016.

So to recap, the government don’t have enough specialists, they’re not training enough despite having too much raw materials (medical graduates), it takes too long for them to train specialists, and when they finally get new specialists, the older ones leave them for a better life.

Aiyo so sad wan. So how to solve this problem?

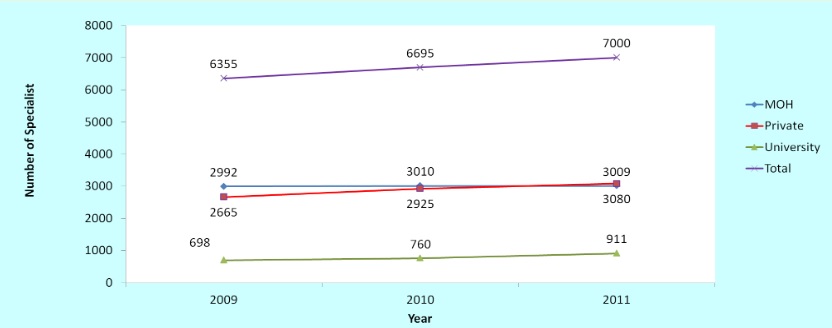

As we’ve discussed at length in this article, so many things contributed to the problem, from the time medical students graduate all the way to when they work as specialists. While the government had been trying several things to ease the process, from shortening the housemanship time for excellent doctors to gradually increasing the slots available for both the Masters’ program as well as housemanships. While the number of specialists have increased slowly over the years, the government is still behind its target.

But before we start organizing another protest in front of the Parliament and drawing up petitions on Change.org, specialist shortage is not a uniquely Malaysian problem. All over the world, countries like the US, Japan, Mexico and even Singapore are reporting that they don’t have nearly enough specialists to serve their people.

So address the problem, Japan, for example, is planning AI hospitals, where software takes the burden of admin work from specialists. Mexico plans to address their shortage as well as uneven distribution (specialists only hanging out at posh cities) by stimulating migration to non-urban places and increasing the salaries of specialists in general.

As for Singapore… they’re actually encouraging their doctors to specialize in being general, emphasizing on treating the patient as a whole, especially those with multiple conditions who would be seen by more than one specialist anyway.

“We should not be in (medicine) for prestige, financial rewards or fame. We should not seek to be a super-specialist when there is limited demand for such capabilities, or choose a speciality primarily because it gives us a good work-life balance.” – Benjamin Ong, Singaporean MOH’s director of medical services, to the Straits Times.

Also, they brought in more than 2,000 foreign doctors into their public hospitals back in 2014. So that’s that. Regardless of all that that’s that stuff, so far we’ve only talked about the government part of the equation. No matter how much incentives are in place, it will all be meaningless if doctors themselves don’t want to specialize in the first place. But that’s kind of an innate thing, isn’t it?

“Only those who are really passionate about their career will push on and persevere to become a specialist… It is only certain specialists who do well. The perception is that all specialists are doing well. Yes, many of them are comfortable but they work very hard.” – Dr Sng Kim Hock, to the Star.

- 3.1KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn18

- Email28

- WhatsApp88