UK English textbooks M’sian school kids next year? We find out if our England got that bad or not

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.4K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn9

- Email9

- WhatsApp42

Recently, the Education Ministry announced that Malaysian school kids will start using only imported English textbooks starting next year. Only students from tadika, primary one and two, and secondary one and two will be affected by the change.

“This is part of the ministry’s English reform to ensure students achieve proficiency levels aligned with international standards. The ministry will buy off-the-shelf books to cater to schools because locally produced textbooks are not able meet the new CEFR levels,” – Deputy Education Minister P. Kamalanathan, quoted from The Star

The “international standards” that the deputy minister mentioned is the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, which Prof Dr Zuraidah Mohd Don from Universiti Malaya said has become the “de facto international standard” for language education, because it is based on decades of research and used not only in Europe, but other countries as well.

Wah, the school kids want to learn speak the powderful English? They ready or not? We try to investigate Malaysia’s English standards, and attempt to find out whether this might be a good or bad thing.

Malaysia is ranked number 12 in English proficiency worldwide!

According to EF English Proficiency test, the world’s largest English proficiency ranking, Malaysia was ranked number 12 out of 72 countries surveyed, and ranked number 2 in Asia, just behind Singapore. The survey found that on average, women tend to score better than men across the world. The survey gathered an average of 13,194 participants from each country, and participants took an online English test.

Of course, that makes the result not entirely representative of Malaysia, as only people who have internet and are interested in testing their English level would be included. The test also seemed to exclude countries that obviously/ primarily speak English, among them are such as US, UK, New Zealand, Canada and Australia. Another piece of news would also go against this seemingly high ranking.

In a 2016 survey, the Malaysia Employers Federation (MEF) found that more than 90% of employers indicated graduates should improve their English proficiency to become more employable. A Jobstreet survey published in 2015 found that poor command of English was the second biggest reason why fresh graduates don’t get the job. Then there was also the time when Malaysian Medical Association reported that about 1000 medical graduates give up on becoming doctors because of poor English.

“After the third response, I got irritated and asked him ‘what’s your problem?’ He said he could understand my questions but he could not speak English, and we’re talking about a university graduate where everything else looks all right on paper,” – MEF executive director Datuk Shamsuddin Bardan recalls his experience to The Star

The root problem might be out of reach of teachers and English books

Undoubtedly, English proficiency is a very important skill in many fields. Access to politics, commerce, the economy, society, and education is dependent on a person’s mastery of English. But learning the language can be a difficult process, and factors such as social and cultural background can make a big difference in terms of providing a conductive environment for students. A study by 4 linguists from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) helps put that in context.

Their qualitative study was published in the Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, and part of it looked at how the spoken language of a Malaysian could affect how others perceive them. They interviewed 20 Malaysian undergraduates of the 3 major ethnicity, and found out how speaking English was viewed in their respective communities.

Among the Malay community, speaking English (also known as “speaking”) can be perceived as “being less Malay” or “un-Malay”, and kids can be shunned because of that. Among Chinese and Indians, speaking English doesn’t seem to evoke the same response, but Chinese and Indian students can be ostracised due to the poor mastery of their mother tongue.

“When they see Chinese they expect us to speak in Mandarin as well, so when we don’t, there’s immediately a sort of boundary there … a barrier there.” – participant Cherry, quoted from the study

Despite that, most students agree that English is important to a certain degree. It’s even seen as a language of a higher social status. Here are some excerpts from a separate study conducted on 30 Form 2 students in 2014.

“……when kita boleh speaking English….automatic kita(we) feel that kita ini pandai (we are intelligent)…..(with laughter) and all our points look good” – a Malay student told the researchers

“bila guna Facebook (when using Facebook) or Tweeter or texting, I use English most of the time because mostly all short forms are in English and easy. ” – A Chinese student told the researchers

“I always feel that even though we don’t speak English so much at home or with friends, English is still important because when we are goggling something on the internet, all the info is in English and that makes me feel that it is important to know and use the language….specially for my later time……..” – an Indian student told the researchers

Concerns for grades and BM is making it hard for English to be widespread in schools

If you remember, the Education ministry ended the policy of teaching science and mathematics in English just a couple of years ago. The gomen found that the academic grades in science and maths have fallen since the change to English. Students in rural areas, who are mainly Malay, suffer the most because of their low English proficiency.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a complete failure but it has not achieved the desired objectives that it was supposed to achieve,

The government is convinced that science and maths need to be taught in a language that will be easily understood by students, which is Bahasa Malay in national schools, Mandarin in Chinese schools and Tamil in Tamil schools.” – former Education minister Muhyiddin Yassin, quoted from The Guardian

Even then, the option to continue using English for science and mathematics under the Dual Language Programme remained opened, if they schools met certain criterias, and had the necessary support from staff and parents. Last year, 279 schools opted for it.

At the same time, there are certain Malay nationalist groups who worry that the position of Bahasa Malaysia would be neglected, or worse, become extinct. Back in 2009, there was even a street protest against the use of English to teach maths and science, that got to the point where riot police had to disperse the crowd with tear gas. Last year, there were even groups that protested the dual language programme with a cardboard coffin.

All this makes it easy for people to believe that the whole English thing is a political issue, rather than a educational one.

“They decided to buckle under the pressure from the Malay Nationalist who argue that by teaching students in English you are neglecting the position of the national language,” – Professor James Chin, head of school of arts and social science at Monash University, quoted from The New York Times

Digging a bit into language extinction, it’s true that a more “valuable” and widespread language can push other less spoken languages towards extinction. But, extinction only happens when not even a single person who speaks the language is left on Earth. Currently, thousands of language face extinction, but there are cases where language “evolve”, like how Latin developed into French and Italian, and also cases where languages merge to created a new one. Much like Manglish, in a way 🙂

“Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn”

The quote by Benjamin Franklin applies very aptly to learning a language. There is no doubt that English will remain an important language, and it’s obviously very important for learners to listen to and speak the language they are learning. For that, quality books and quality teachers will only be part of it, but an environment that doesn’t stigmatise weak speakers is important too.

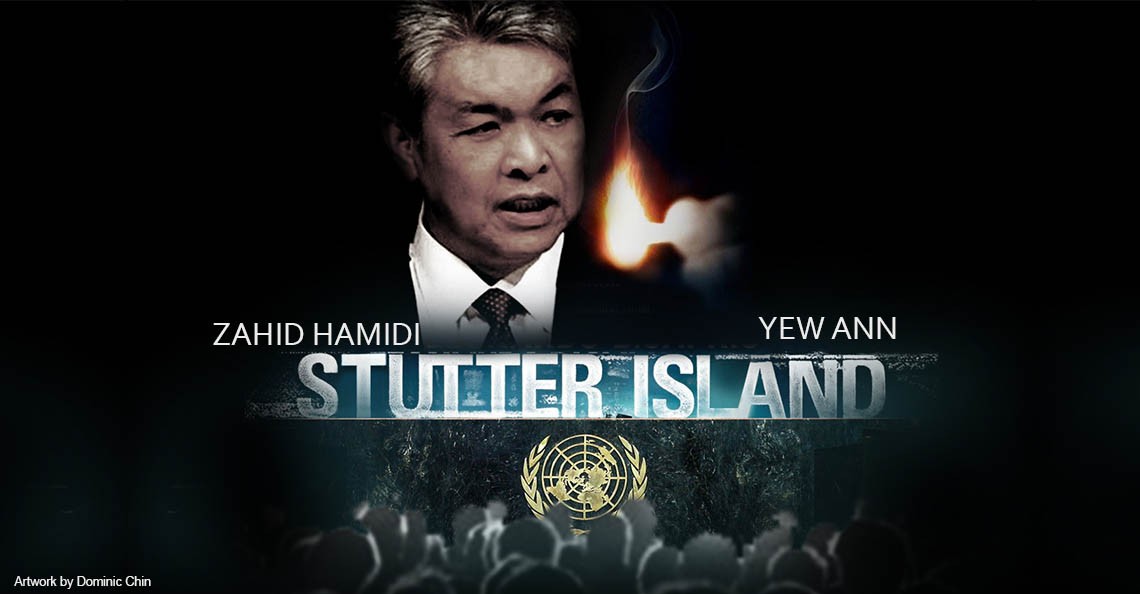

Around the end of September last year, Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi was criticised and ridiculed for his speech at the UN general assembly. We know because we hopped on the bandwagon too.

While it was sad to see a high ranking official stumble his way through an international conference, the type of jeering is not exactly encouraging message we want to be sending out to students that are learning the language. On the contrary, it was actually quite commendable for the Deputy Prime Minister to choose speak English at the assembly.

The gomen is addressing the concerns raised over the international English book matter, and will also look into training teachers to fit the standards of the materials used. But as normal rakyat who don’t have direct decision over the matter, the least we can do is not pour cold water.

“Never discourage anyone…who continually makes progress, no matter how slow.” – Plato, dead but famous Greek philosopher

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.4K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn9

- Email9

- WhatsApp42